LIQUEUR WINES

Liqueur wines are produced from a base wine with a natural total alcoholic strength of not less than 12 %, which may undergo cold concentration or be enriched with mixture, ethyl alcohol, wine spirits, concentrated or cooked must. The total alcoholic strength is always high, but must not be more than twice as high as the total alcoholic strength of the base wine, while the alcoholic strength must be between 15 -22 %. The sugar concentration is also high, not less than 50 g/l, except for dry or dry fortified wines.

MISTELLA = product obtained from a must with a total natural alcoholic strength of not less than 12 %, made infermentescible by the addition of ethyl alcohol or spirits and brought to an alcoholic strength between 16 % and 22 %. It is used for the production of Marsala.

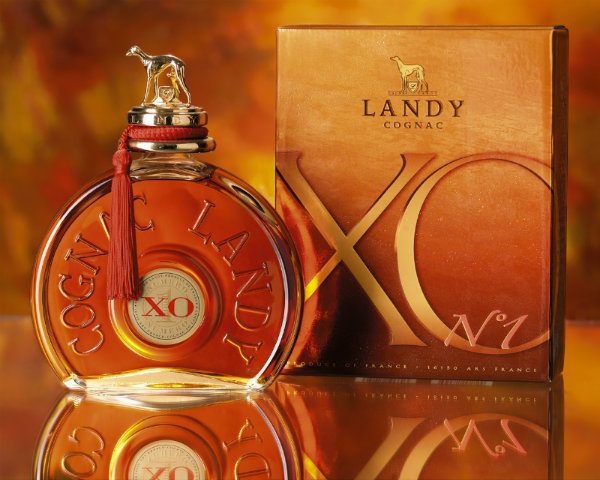

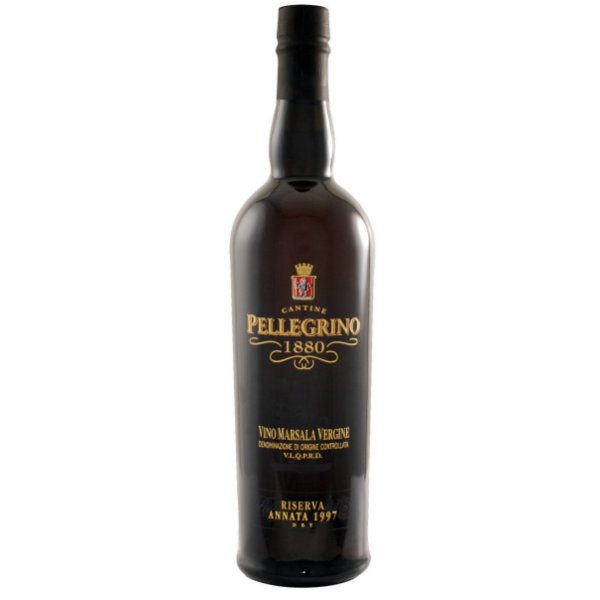

Marsala

SOLERAS METHOD = the barrels are stacked in rows of 3 or 5, from those placed on the floor (solera) the wine that is considered to be ready is tapped and replaced with the wine taken from the barrels above, considering that about 2-3 % per year is lost through evaporation. In this way, if the process had started even 100 years ago, there would always be a part, even a small part, of the wine from the harvest of 100 years ago in the solera barrels, if these have never been emptied.

Specifications since 1984 classify Marsalas according to colour: Gold, Amber and Ruby and precisely indicates the grape varieties to be used, the alcohol content, the years of ageing and the residual sugar content (dry 100). A DOC wine produced in the province of Trapani, it is made from Grillo, Cataratto, Bianco comune, Cataratto bianco lucido, Damanzino and Inzolia for the Ambra and Oro types, while Pignatello, Nero d'Avola and Nerello mascalese are used for the rarest, Rubino, which contains a maximum of 30 % of white grapes.

Ageing:

- FINE: min 17 % vol, min 1 year ageing;

- UPPER: min 18 % vol, min 2 years ageing;

- SUPERIORE RISERVA: min 18 % vol, min 4 years ageing;

- VIRGIN and/or SOLERAS: min 18 % vol, min 5 years ageing;

- VIRGIN and/or SOLERAS STRAVECCHIO or RISERVA: min 18 % vol, min 10 years ageing;

Marsala is a CONCHED WINE because cooked must, ethyl alcohol of vinous origin (3-5 % under the control of the Guardia di Finanza), brandy or a mixture in different % depending on the type can be added to the base wine.

The resulting wine is placed in 300-400 litre oak or cherry casks left drained, i.e. only 2/3 full to encourage a series of oxidative processes protected by the high alcohol concentration.

BLENDING = skilful blending of wines from different vintages for which there is obviously no vintage. Aged in warehouses at ground level, these wines create a typical bouquet. If stored well, after bottling, they can last for decades.

Marsala is best enjoyed chilled, 12-14 °C, in small tulip-shaped crystal glasses. Perfect for meditation, it can be served with some desserts. The Vergine and dry Superiore, if very fresh, are perfect for an aperitif with various savoury snacks, but can also accompany some shellfish dishes with tasty sauces. Superiore can be paired with foie gras or blue cheeses such as Gorgonzola, Roquefort, Stilton. The sweet Marsala is perfect with chocolate pralines.

The origins of Marsala date back to the Phoenicians and the Carthaginians who introduced vines to the Mediterranean. Excavations in Mozia, a tiny island in front of Trapani, show that even in ancient times wine was transported in terracotta amphorae with a pointed base to facilitate loading and stability in the holds of ships. The name derives from the Arabic Marsa'Ali (port of the prophet) or Mars-el-Allah (port of God), but the real invention of this wine is due to the English in 1770.

John Woodhouse, a Liverpool shipowner, traded in the area. Having an excellent nose for business, he realised that the wine was rich enough in body and ethyl alcohol to please the English and to prevent the wine from spoiling during the voyage he added a little whisky.

The Napoleonic wars made it very difficult for Spanish and Portuguese wines to be shipped to England, which ceased altogether at that time. Marsala in England was so successful that John returned to Marsala to set up his own baglio (: building with court) with the white oak barrels he had brought from England. As the Marsala trade expanded, other English merchants arrived in Marsala, first his cousins then Ingham, Hopps, Glasgow, Whitaker... who created a true English monopoly of Marsala. Admiral Nelson loved it and before leaving for the Egypt expedition he sent an order to Malta for 40,000 gallons of Marsala (200,000 litres).

Marsala, by now the wine of the English, had great fortunes throughout the 19th century. But Madeira and Port, also of English origin, were returning to the market competitive in quality and price and Marsala began to lose share. In those years, the Florios (a noble family of Calabrian origin who had become very rich in Palermo at the turn of the 20th century), with a merchant fleet of 99 ships, began exporting their Marsala to Brazil, Argentina and the United States. As the British were increasingly intent on abandoning the production of Marsala, the Florios first bought the cellars of Woodhouse and the Inghams, then of all the others, and linked their name forever to the production of Marsala.

Sherry

Produced using the soleras method in the area around Jarez de la Frontera in sunny Andalusia from palomino de jarez (the yeasts that create flor during barrel maturation develop on its skins), pedro ximénez and moscadel vines. The albariza soil is rich in calcium carbonate and has great absorbent power, which tends to form a hard white crust under the heat of the sun that limits the evaporation of water.

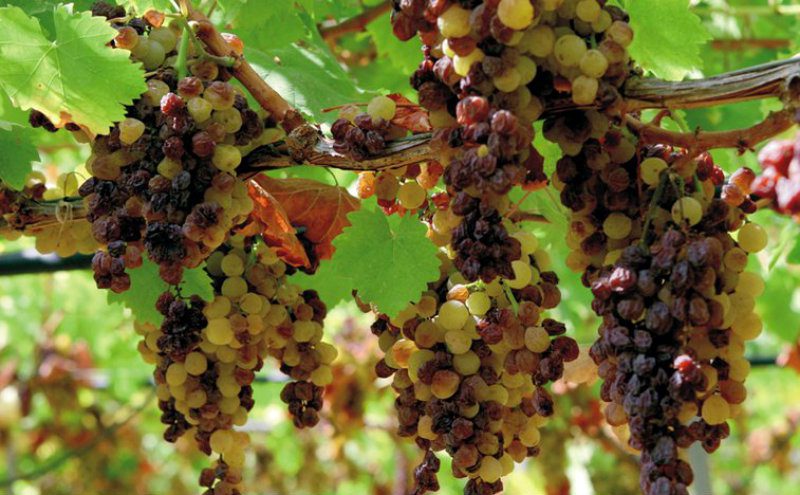

In the past, the grapes were dried on racks, a few hours for the palomino and three weeks for the pedro and moscadel. Today, the palomino is harvested a little later and only the other two receive a short drying period. The grapes are pressed using modern horizontal presses and fermentation is almost always carried out in steel containers. The resulting white wine is dry, with an alcohol content of 11-12.5 %, but if pedro or moscadel grapes are used, the sugar content is higher.

After alcoholisation to at least 15 % in ethyl alcohol for the Fino and 18 % for the Oloroso, the wines are placed in American oak botas of approximately 600 litres, although they are filled to a maximum of about 500. The number and frequency of racking will affect the character of the wine.

Up

- Up pale straw colour, notes of yeast and almond;

- Manzanilla made in Sanlucar De Barrameda, very dry, savoury aftertaste;

- Amontillado dry, partial flor development, soft, structured, intense amber tones and strong dried fruit aroma.

Palo Cortado

dark, made only with exceptional wines, it is somewhere between Fino, whose delicate, pungent perfume it recalls, and Oloroso, to which it is more similar in smoothness.

Oloroso

without flor development, very fragrant, among the strongest and softest, with a mahogany colour and a pronounced nutty taste.

- Oloroso dry and semi-dry

- Sweet Oloroso Doux

Cream

- Creamis out of the specification: it is an oloroso with added sweet or muted must of Pedro Ximénes, with a very dark colour.

- Pale Cream sherryfino with the addition of dulce pasa, which is a palomino grape must also having up to 50% of sugar and with wine alcohol added up to 9%;

- Moscatel: partially raisin sherry.

Pedro Ximénez

is the sweetest and richest, obtained from grapes of the same name that are dried. It can rest for decades in casks then in bottles. Shiny black in colour, the very intense aroma is reminiscent of caramel, dried figs and tamarind, dried fruit and sweet spices, chocolate and dates. The sweet and mellow flavour fades into a very long and complex aromatic persistence. It goes well with richly structured desserts, cocoa and dried fruit and chocolate.

The botas of the Sherry Fino are kept drained, filled to about 5/7 of capacity to encourage the development of the film-forming yeasts in the air and thus the formation of flora. If maturation takes place under the protective blanket of flor, as long as the ethyl alcohol does not exceed 15 %, the Sherry is not affected by the action of oxygen, the colour remains clear and the aroma is more delicate. If the alcohol exceeds 17 %, the flor breaks down and the ageing becomes oxidative, resulting in brown hues and very different aromas.

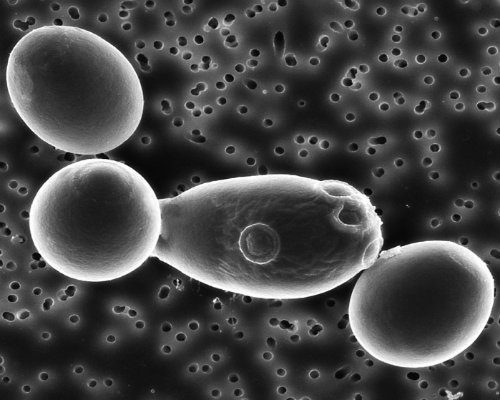

The saccharomyces ellipsoideus not only ferment the residual sugars, but also reduce the glycerine and form aldehydes, ethers and acetals that make the aromatic bouquet of Sherry very special. The evolution of Sherry in the botas takes place using the SOLERAS method: on the first row of barrels placed on the ground are the first and second criadera, with the youngest wines. Each year a little wine is tapped from the soler a, replaced by that of the first criadera and so on, in barrels generally consisting of seven criadera, although for some Manzanillas there are as many as 20.

Porto

Produced in the upper Douro valley, it is aged in the historic city of Oporto, specifically in Vila Nova de Gaia. It is made from more than 50 black grapes (the 60% is bastard, with high yields and a strong alcohol component, the touriga nacional has elegant fruity notes and the touriga francesa has herbaceous notes, the tinta barroca is very smooth and the tinta roriz very elegant) and white grapes harvested very ripe and rich in sugars, colouring and aromatic substances.

The must, obtained with modern crushers, is fermented at a controlled temperature of around 30 °C. Having reached 6-7 % of ethyl alcohol, Brandy or wine alcohol is added to stop fermentation more or less quickly depending on the desired degree of sweetness (1 to 3 days). Then the Port is put into traditional 550-litre pipes and left to rest for a couple of months, proceeding to a first racking and a possible second addition of distillate. Since 1986, small producers have been able to age and bottle Port directly in the Douro.

Reportage on vinho do Porto

Vinho do Porto can, somewhat inaccurately, be described as an invention born of an English need. Between the 17th and 18th centuries, the climate of tension between England and France blocked the latter's wine exports and the English had to 'fall back' on Portuguese wines. Hence began the trade and the history of many Cave do Porto, which still bear the names of their overseas founders. Of this Northern Capital embraced by the fury of the Atlantic, so mystical and reserved, I will tell you about the character and cunning with which it has been able to exploit a wealth it does not possess, but which has made it famous throughout the world: vinho do Porto. And I will do so from the point of view of its wineries, faces capable of telling you the same story with different expressions.

Madeira

Madeira is a fortified wine produced in the Portuguese archipelago of Madeira, about 700 km west of Morocco. Since before 1600, a normal wine was produced from verdelho and malvasia grapes, which filled the holds of merchant ships bound for the New World that used to stop on the island for provisions, but arrived at their destination completely undrinkable. In order to prevent this, it was thought to add brandy to the wine so that it would endure the pitfalls of the long journey. The wine would remain in the barrels to mature for months in the equatorial heat of the ships' holds, and the preservative action of the alcohol would return, at the end of the long voyage, an excellent wine, with character, totally different from the original one. Thus was born the myth of Madeira, whose practice of letting it oxidise in the equatorial heat became so indispensable that, at the time, the best Madeiras were precisely those that had travelled for months in the holds of ships and were therefore called Vinhos de Roda, that is, wines that had travelled all the way back, enriched and embellished, to the island. Today, the process is carried out with estufas, steel/stone stoves or rooms heated up to 50 °C that quickly oxidise the wine, giving Madeira its characteristic flavour. Exposure to high temperatures and oxidation favour the wine's stability; an open bottle of Madeira will retain its organoleptic characteristics for many months. If properly bottled and stored, Madeira is one of the most long-lived wines, able to be drunk even after hundreds of years.

Sercial (dry)

Ideal as an aperitif, it is produced from the vineyards of the highest terraces and is characterised by its amber colour, acidity and aromas, and dry and delicate taste.

Verdelho (semi-dry)

Dark colour, smoky notes, hints of honey, good structure and good residual sugar make it perfect drunk very cool as an aperitif or after dinner.

Bual (sweet)

Obtained from this very rare grape, it has a sweeter, more structured flavour anticipated by a brown, glossy colour and an intense, almost burnt perfume. Perfect for after dinner and dessert.

Malmsey (rich)

A meditation wine, it is the rarest and is made from Malvasia grapes grown near the sea. Unmistakable aromatic notes of caramel and honey and a rich, sweet flavour.

VITICOLTURE EROICA = Madeira is a predominantly mountainous island and in the past was one large forest, so much so that, when it was discovered, it was necessary to set fire to the forest in order to land. Today, the vineyards are developed on a series of terraces on volcanic soil, with a subtropical climate and dense vegetation where, taking advantage of every possible square metre, the main varieties that give name to the different types of Madeira are cultivated, namely: Sercial, Bual, Malvasia and Verdelho. Viticulture initially appears to be a nightmare, with a dreadful hot and humid climate, pergola cultivation and grapes in perennial shade that leads to them being harvested unripe because they never ripen. The law imposes a minimum 9% of potential alcohol, but the low alcohol content due to the very low residual sugar is not an obstacle thanks to the fortification of the wine, while the intrinsic acidity of the berries is fundamental to conferring freshness in a wine that, by morphology, would otherwise be too sweet.

All my notes on 'How wine is born'...