This article is a tribute to Roberto Bellini, who was able to masterfully immerse me in the heroic viticulture of the Ribeira Sacra. Reading the new issue of Vitae, the wonderful A.I.S. magazine that I receive quarterly, I thought it was a shame not to share it with you. And if it can be a way to introduce you to this wonderful magazine that alone is worth the A.I.S. membership fee and give you a little extra motivation to join us, I will be very happy. You might think I was a fool to rewrite everything by hand, but I thought it was really worth it. It took me hours to write it, to select the photos and adjust them to give you an even sharper view of this extraordinary story and for that I ask you to be so kind as to thank me by sharing it on twitter 🙂 🙂 I'm going to give you a little extra motivation to join us.

[Tweet "Journey to the Ribeira Sacra in homage to Roberto Bellini #AIS #Sommelier #Vitae #Vino"]

Roberto Bellini, Sommelier and author of the A.I.S. Vitae magazine, met wine professionally in 1977. He managed a Chianti winery for many years. In the meantime, he followed AIS training, also updating himself with specific Masters on Whisky and Champagne, as well as with the Master of Wine institute admission seminar. Several times national councillor of the A.I.S., member of the National Executive Council and Vice President (1999-2002 and since 2010). He collaborates with specialised magazines and writes about wine such as Toscana Libera Terra di Vino (1999), Champagne e Champagnes (2009). In 2005, he was the first Italian to win the title of Ambassadeur du Champagne Italie.

Source: Vitae n°102 March 2015

Beginning in 218 BC, the Romans began their expansion into modern-day Spain and ended the war effort around 19 BC. Among the areas most reluctant to subjugate were those in the north-west, including the Ribeira Sacra: once conquered, they were immediately exploited to plant vineyards, having been identified as ideal slopes for ripening grapes. The Ribeira Sacra is a slice of land where history has left notes and hints of memory without much archaeological evidence, but has maintained an environmental virginity of immense naturalistic value.

Today's region is Galicia, which, when it comes to viticulture, was relegated to the fringes of oenological fame until the Albariño and DO Rìas Baixas, whose best sub-zones are Val do Salnes, Condado de Tea and O Rosal, exploded a decade ago. It was in fact the Rìas Baixas that brought a bit of renewal to the sleepy world of Spanish white wine, often relaxed in a prolonged siesta. More than wine, religion could for this region, given the presence of Santiago de Compostela and all the caminos that touch and cross the forests and vineyards of this rugged and verdant territory. Ribeira Sacra is a bulbillo of soil wedged between the Valdeorras DO to the east, Ribeiro to the west and Monterrei to the south, while leaving the aromatic elegies of the Albariño in the oceanic distance. For the French it would be a cul de sac, for us Italians a road without a backdrop.

Yet this non-existence should not be interpreted as oenological negativity, but rather as a safe of historicity, perhaps of sacredness. Could this be why Ribeira is 'sacred'?

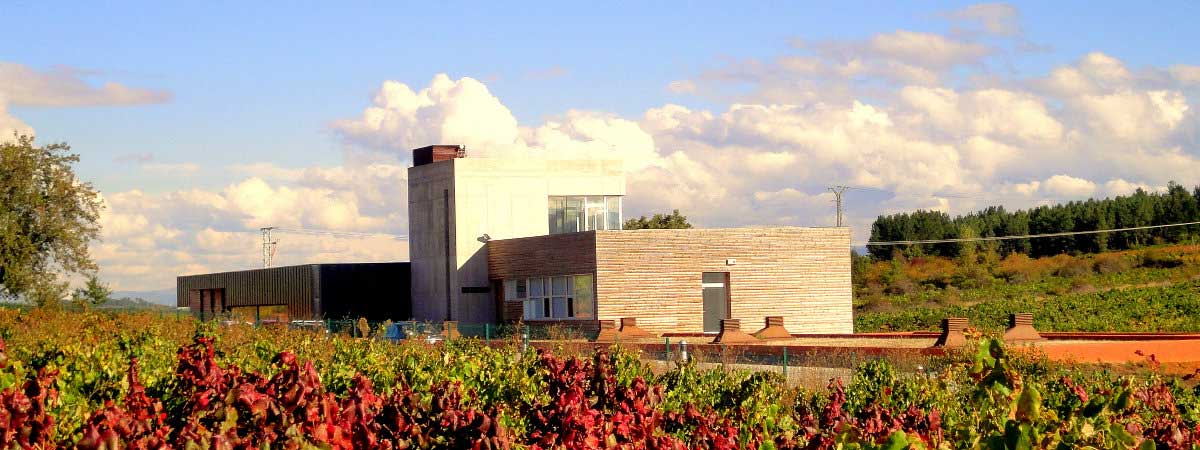

The wine-growing area could be described as quadri-fluvial, effectively coining an innovative aquatic intersection, when contextualised in the viticultural environment. The Rio Miño descends from the north, the Rio Sil flows from the east and the Rio Cabe from the north and the Rio Bibei from the south flow into it. Extremely pure waters, refreshing to the environment, capable of excavating and shaping the hard granite and black slate to such an extent that they create worrying and dangerous coastlines called ribeiras: portions of land that are not very hospitable, tiring to work and stingy in their agronomic yields, lands that starve the campesinos. Told with this preface, it would all seem to be a poetic luxuriance of life past and present, but it was not so.

It goes without saying that the Romans exploited it viticulturally to support the march of the thirsty legions to the ocean shores. The terracing was a gamble at the time, being - and still is - a carved notch carved into the hard rock stratum, unfit for a couple of pruners, let alone a pack animal useful for alleviating the suffering of the exhausted peònes. Some vineyards were even only accessible by river.

The primordial wine-growing projects of the Romans were followed by the monks who, between a prayer and an indulgence, a miserere and an extreme unction, continued the work of daringly terracing the shores of the Sil, Miño and Bibei rivers. It was hard and heavy work, based only on the natural strength of the muscles, a climb that crushed the legs, disarticulated the spine and, at the end of a hot day, the face was the red colour of a boiled lobster, while the brain boiled.

In spite of the enormous difficulties, the agricultural harshness of the land was guarded with alternating, more or less fortunate, fortunes for almost two thousand years, then two devastating cataclysms struck: phylloxera and the Civil War. It was a destructively deadly coupling, the greedy and evil aphid sucked the life out of the roots of the vines, while the Civil War devastated the territory not only in a material way, i.e. economically, but also psychologically. The new generations could not withstand the ravages and emigrated massively, the land was left untended and the terraces planted with vines were abandoned. The surrounding brushwood took back the soils stolen over the millennia, the terraces were sucked and crushed by the force of nature and the landscape began to shift as in Ambrogio Lorenzetti's frescoes Allegory and Effects of Good and Bad Governanceand we all know what nefarious effects bad governance can have!

There is no better refrain to match the vicissitudes of these vineyards than that from the Bruce Springsteen song Atlantic City from the album 'Nebraska' (1982): 'Everything dies, baby, that's a fact, but maybe everything that dies someday comes back'. And those 'dead' vines are reborn! A surprising and unexpected resurrection, but full of an energetic will for revenge on the misfortunes that the past had reserved for those humble people. An ignition of new agricultural desires, which the màs ancianos de la comarca galiziana initially viewed with pessimistic scepticism. Yet everything has been reborn, the terraces on which the vine grew have been restored or rebuilt and wine has been produced again: viva el vino!

As it was easy to guess, the difficulty was not that of making wine, there was the question of what the identity and/or personality of the recovered Ribeira Sacra should be: an oenological crossroads that winks at the new world, or a passionate and melancholic dive into the legendary viticultural adventures of the past?

As in a self-respecting fairytale, and equally sharing in the excitement of anticipation, there was no time to ramble or fantasize for long: 'arid land, arid wine' seemed the best combination to get away from the winking fables of an easy future. The Ribeira Sacra, they told themselves, is almost inaccessible. So far from the limelight that even some Galician inhabitants would not know how to get there. Therefore, they valued being on the fringes of knowability, identifying in this a dowry to offer, or perhaps to place with pride and boast on the plate of media scales and beyond. In order to foil this pseudo-heretical individualism, it was necessary to find other atout to spend, so why not distinguish oneself by maintaining the old local vines, playing on the atavistic union that those varietals have with the stratified granite and slate soil, betting on the uniqueness and special microclimates, as well as on the extreme temperature excursions that arise from the presence of water and the rigidity of the coastline, and finally on that desire to do the new with innovative old wines?

Fortunately, the line of old, of tradition, of Romanity prevailed, and not even the popular Tempranillo was allowed. There was also the need to redefine or recover the identity of a wine. A wine this time to be destined for a different market than the one that characterised the history of the area, often for self-consumption, made from a mixture of grapes - pressed in lagares in the vineyard and some even fermented alcohol - with the surplus sold in carats to the bars and restaurants of Lugo by futuristic river transport.

A small and dutiful clarification for all Romagnoli like me: here we do not mean Lugo di Romagna, but the Galician province of Lugo, facing the Atlantic Ocean, whose 355,000 inhabitants are called luguès. And as you can see from this beautiful view of the Cathedral de Lugo, it doesn't really resemble our Romagna town... 😛

In this exuberant enthusiasm for rebirth, winegrowers began to look around, to study wine production in neighbouring areas, to analyse soils in greater depth and to search for possible analogies with other wine-growing realities. The analysis of the wine-growing ecosystem showed that development was very much dependent on fixed factors, while giving the variable factors a much reduced range compared to neighbouring appellations. The climate cannot even be clearly categorised, although it is close to a pure continental condition; there is a partial Atlantic influence and a substantial - but not pure - continental condition similar to Burgundy, while the other condition is a mix of Chablis and Champagne climate. There is, however, a climatic constant because the river ventilation not only relieves the burn of the grapes on the vine during the day; at night it does much more, wrapping them in a cool halo that preserves the aromas contained in the safe of the epicarp.

From these meso- and microclimatic conditions and from the hours of daily sunlight, as well as from what the earth can offer the root system, one cannot chisel wines with structural peaks of imposing tannic and/or acidic muscularity, one cannot colour them with intense colours, one cannot create explosive aromas; everything shifts into lightness of body, into more expressive gustative balance, into velour savouriness and softness, into an olfactory kit to be deciphered in the line of fragrant fruitiness and minerality, rather than in bursting impacts of a single majestic perfume of concentration. Some winemakers of the Facebook era are perhaps going too far in their wine comparisons, even venturing organoleptic affinities close to Burgundy, but certainly not very compatible with Northern Spain.

Ribeira Sacra, which translates as 'sacred coasts', does not reflect any reverence for those rugged vineyards, but instead originates from the fact that the area was dotted with convents, monasteries and churches, a total of no less than 18 structures, and those religious kept vine cultivation alive until well into the 12th century.

Among the grapes cultivated today, Mencía stands out and the future is being rebuilt on this. The bunch shape is medium/small, with compact, medium-sized berries in the shape of an ellipsoid. The problem with this grape lies in the ripening, or rather over-ripening, because it causes a worrying loss of acidity in favour of a prosperous sugar bosom and a flattening of the aftertaste profile. When, on the other hand, ripening develops in a balanced manner, the wine is also painted a dark but bright red, with a predominantly fruity olfactory progression deriving from the semi-aromaticity of the grape, without loss of freshness and with a little tannic shoulder: under these conditions it becomes a red with a certain potential for ageing.

The oenological tradition used to be based on blending, i.e. mixing several grapes, in perfect Northern Spanish style; today, the grapes are fermented separately and then blended. The current trend is to make red wines for medium ageing, trying to bring out the typical Mencía scents, i.e. blackberry, raspberry, undergrowth, wet slate; there are those who opt for barrel ageing, even new ones, but without overloading the tertiary contribution. Normally there is a need to control the power of the soft side of the wine, since the tannins of the mencìa create a good structural volume, but lack wrinkled intensity, leaving space on the palate for the 'sweetness' of the fruity flavour and mineral savouriness.

A significant example of this oenological orientation is the wine Ribeira Sacra Lalama of the Dominio do Bibei company. Mencía grapes are used for the 90%, with an addition of garnacha, brancellao and muratón. In the vineyard, the grapes are harvested as they were 1000 years ago, in 10 kg crates; today, however, they make the triad and the varietals are separated. Before processing begins, the grapes (also shelled) are stored in a refrigerated environment between 0 and 2 °C, followed by fermentation in wooden barrels of various capacities and stages. Maceration lasts for two to three weeks, malolactic fermentation is carried out completely, followed by maturation in non-new wooden barrels with capacities ranging from 45 to 300 litres. Racking and decanting are all carried out by hand. To refresh the wine before bottling and the subsequent one-year vatting, a 15% of the following vintage is added.

The typicality and particularity of the cellar journey should not mislead you, the result is a wine to be drunk in the medium term, because it is at its best until the slight sweet spiciness is overtaken by the jammy evolution of the fruitiness; it is a wine that needs to remain lively in freshness to be appreciated in all its appetising gluttony and to enhance the aroma finish with its natural minerality.

Producers claim that the Mencía grape, with its faithful squires, is capable of producing wines with two distinct characterisations: oceanic and mountainous. Oceanic Mencía has an organoleptic profile expressed in density. Chromatic density, olfactory opulence with greater exoticity and fruity syrupiness, the vegetal transforms into balsamic dryness and vanilla floats over minerality. Dense is the palate, with gustatory volume interwoven with alcohol and tannin in harmonious fusion, the juiciness of the fruity flavours seems to soften into an exhausting aromatic resistance of boric herbs dried in the verano caliente. The Mencía montanara has a wild character right from the colour, but more on the nose because its fruity scents are woody; blackberry, raspberry, marasca cherry and carnelian. The vegetal scent sphere is of mountain undergrowth, a little fern, a little mushroom, with a more rocky, earthy minerality. It has a taste-olfactory trajectory that is a little scorbutic in freshness, tingling in minerality, the taste finish is filled with the flavour of refreshing raspberry and morello cherry shakes and closes with a something of bitterness that recalls, they say, the taste of wine from 2000 years ago: it is like drinking history!

The ampelographic games are defined, so the future of Ribeira Sacra is projected in the exaltation of the Mencía grape, to extract from its bipolar organoleptic identity the best and most expressive parts of each. They will not be easy to find, but some wineries have managed to carve out a niche for themselves in the wine boutiques of nations with few or no heroic qualms, such as the Anglo-Saxon and North American markets. What is astonishing about the area is the rigorous interpretation of the eno-spiritual essence of the grape, which combines with the experimental winemaking spirituality of the cellars, for a final expression loaded with a wealth of innovation on eno-archaeological findings: these shine more courtly with new technical and viticultural insights than with a rigid application of past concepts.

These country folk deserve praise for having prevented the roots of a thousand-year-old viticulture from being forever robbed of the solid sap of a terroir that is more unique than exceptional, capable, in its own rebirth, of not having allowed itself to be bewitched by the fabled oenology of cabernet, chardonnay and the like. One example: the Bodega Ramon Losada. Over the centuries, the Losada people produced wine from the grapes grown on their terraces for their daily needs and sold the surplus in the surrounding towns. This did not produce enough profit to keep the terraces intact, so the decay was progressive and inexorable. In the critical years between 1940 and 1950 they emigrated to South America. As good Spaniards they cultivated a healthy nostalgia, so much so that they retraced their steps in 1990, also finding unpleasant surprises, such as part of the terraces being submerged by the construction of a hydroelectric dam. Ramon Losada recovered the old terraces of Roman origin and identified in a handkerchief, just under one and a half hectares, a spectacularly ideal site for the Mencía grape, by virtue of the slate in the subsoil and the steep terraces overlooking the river Sil; The result is Viña Caneiro, a wine that blends, in an unusual way, exotic fruit, spices, minerality, gourmand in the sip, substantial in its juiciness, voracious in its freshness due to the breezes of the Sil. A timeless wine that has crossed its own time: for the Losada family, Mencía Viña Caneiro is the taste of 2000 years of history. In an area of viticultural and oenological rebirth and reconquest, where the sense of the past is permeated in the organoleptic essences of the wines, and the new - not only technique, but also marketing - gives a boost of visibility to a land that had retreated into a viticultural enclave and is now building the image of an indigenous and alternative Ribeira.

Roberto Bellini

Source: Vitae Magazine, No. 102, March 2015

Hoping that this story has enriched you as much as it has enriched me, I embrace you.

Chiara