Today and tomorrow I dedicate them to studying because this Friday I have my last university exam of the second year: Microbiology of Food and Wine. A complex subject that I am enjoying beyond expectations: I am learning really useful things about wine yeasts in particular. I had long realised that yeast plays an important role in the sensory characteristics of wine, but only now can I tell how the various strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae! I was reading my e-mails this morning when I found a message from Quora inviting me to read the reply of Francesca Sau, graduate in intercultural linguist mediation at La Sapienza in Rome, to the question "What people ate in theVictorian Era that today would be considered strange?". An answer (I give it to you in green) so beautiful that I want to share it here on my wine blog and on which I want to make some final reflections. And which you will see is more pertinent than you think to the very subject I am studying!

Victorian Era: a short introduction

In Victorian times, urbanisation grew very fast, leading to large numbers of people living in cities. Consequently, the demand for food also grew. However, there was still no control over the food production chain and its wholesomeness, besides the fact that science did not have all the answers we have today on how bad certain additives could be. What the Victorian merchants were interested in was profit: they lowered the cost of raw materials and raised the selling price. This led to the adulteration of food with ingredients that were cheaper, but which we would not consider edible today.

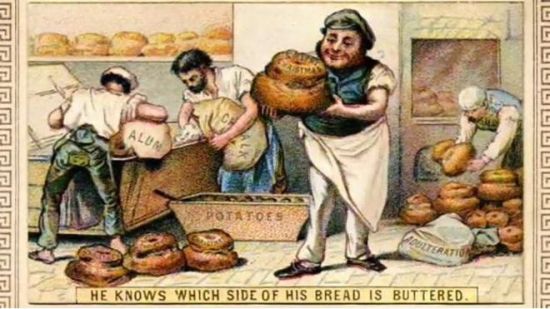

Victorian era: bread

One of the most adulterated foods of the Victorian era was bread. A compound that today is found in some detergents was mixed with the flour: AlK (alum). It had the property of making the bread whiter, but also of retaining water, making the bread more 'compact' and dense. In small doses, it was not dangerous, but if those who produced the flour added it without any control, and so did the baker after him, the amount contained in the final product could become a great health hazard. Another additive was 'simply' chalk dust. It is estimated that often in a Victorian loaf of bread 1/3 of the total was not flour, but additives of this kind. Housewives of this period, contrary to our passion for the most natural and wholesome looking foods, would ALWAYS have preferred the whitest loaf of all, hence adulterated. It is easy to understand how easy it was for a worker of that time to become malnourished if his diet was mainly based on this bread, 1/3 of which had no nutrients at all and charged as much as 'normal' bread. Moreover, these ingredients caused chronic gastritis in adults and even death in children, as they altered the normal functioning of bowel movements and caused severe diarrhoea.

Victorian Era: the cult of beauty

Another reason for adulterating food was to make it more beautiful to the eye. So they started using a whole range of substances to give food an inviting colour. For example, mustard was made more yellow and cheaper (for those who produced it) by adding lead chromate. The same as is used today to paint the American school buses we see in the movies: a very, very bright yellow.

Victorian Era: the five o'clock tea

The tea was adulterated by anything: iron filings, various powders, already used tea leaves plus lead to make it look black, and green tea contained Prussian blue.

Victorian Era: milk for children

One of the greatest health risks lurked in one of the most popular foods of the time, especially in children's diets: milk, the most important and cheapest source of calcium, a food considered important in the diet from a health perspective. In 1882, 20000 milk samples were tested and 1/5 of the total had been adulterated. In general, however, this adulteration was actually known and considered beneficial. The milk that arrived in London was almost all treated with boric acid, also known as borax. At the time, it was believed that the addition of this compound to milk could 'purify' it by postponing the date when it would go bad or by turning expired milk into good milk.

Milk when good has a neutral pH of 7. When it goes bad, the pH becomes acidic. The addition of borax would bring the pH of the milk back to neutral again. By neutralising the acid, the milk tastes palatable again. Borax was also sold in shops and bought in powder form by housewives. Besides adding it to milk, it was used to clean toilets, purify water from bacteria and many other things.

Five grams of borax were needed to neutralise the acidity of half a litre of milk. 5 grams of borax is potentially enough to kill a child. The symptoms it caused were heartburn, vomiting and diarrhoea for small doses, brain and kidney damage for somewhat larger doses, and finally death.

Bovine tuberculosis

The greatest danger lies in an even greater fundamental error: borax is not capable of killing bacteria as was thought, but only of masking the taste. One of the bacteria that remained in borax-treated milk was brucella, capable of causing severe fevers that last for weeks. But the most terrible bacterium that spread because of borax was bovine TB. Bovine TB is also called non-pulmonary and damages internal organs and bones. One of the most terrible effects of TB is the formation of abscesses in the spine. Abscesses make the bones of the spine more fragile, causing them to collapse. If several vertebrae are compromised, the result is a severe deformity. LThe abscess and collapse of the spine put pressure on the spinal cord and the consequences are paralysis and death.

All Victorian children, from all walks of life, are considered to have been exposed to this bacterium at some time during their growth. Many of them died. Hundreds of thousands of children.

My thoughts: what has changed?

In about ten minutes I'll be back to brush up on microbiology. Among the things I am studying are the risks of contamination during the production, processing, transport and storage of ingredients that reach our tables and restaurant counters.

Pistachio and salmon ice cream

The first point I want to make is that even today there is a cult of beauty and I believe that very few people prefer the less tempting food over the more 'showy' one. Let me give you a couple of classic examples of two foods I adore: pistachio ice cream and salmon. Pistachio ice cream without colouring agents does not have an inviting colour: it is a beige that barely tends to green, very dull. Yet in most ice-cream parlours you find pistachio ice cream in all shades of green. The most commonly used colouring agent is chlorophyll, and it is often used to mask the addition of almonds to the pistachio paste in its cheaper versions. Without going into the issues of food fraud, bagged ice cream (I still shudder to think of the Sigep Fair in Rimini) and really too bright/fake colourings, we are inclined to prefer a pistachio ice cream that is greener than a brown one. And we make the wrong choice.

Things get worse if you love salmon. Farmed salmon sucks and should not be eaten. For goodness sake, it may taste good, especially if we have never tasted wild salmon and if the farmed one has been adulterated in various ways. The feed of farmed salmon contains synthetic astaxanthin, a carotenoid that gives the flesh its pink colour. This additive has the same chemical form as that in which the crustaceans on which wild salmon feed are rich.

Intensive salmon farms are unspeakable because of the cruelty to animals, the risk to the entire ecosystem, and also for health reasons, because eating so many antibiotics causes us to become immunoresistant. This is not combated by becoming vegetarians or vegans, which is not in our nature and has other hallucinating consequences for us and the animals, but consciously choosing what you eat. And the 'wild salmon costs too much' excuse doesn't hold water: rather eat it once less, have one less drink or stop smoking.

(Co)science from the Victorian era to the present day

Beyond the food frauds that existed in the Victorian era, exist today and will always exist, even though we are in 2021 there is a general distrust of scientific progress perpetuated mainly by the less educated. So-called grandmother's remedies or natural remedies are preferred. Yet they are the same ones that killed millions in the Victorian era. A paradox? One fears the synthetic preservative, but does not fear the potentially lethal bacteria that can develop naturally in food. Even in wine it is like this: endless praise is given to natural wines that in almost all cases stink to high heaven - and the stench, ladies and gentlemen, is the nice acetic bacteria and the bunch - but praise is given to the absence of treatments necessary to produce a quality wine, both organoleptically and in terms of healthiness.

Lack of culture was dangerous yesterday and is dangerous today, in this sense nothing has changed. Extreme solutions, from veganism to the consumption of so-called 'natural' products, are not the universal solution in a world increasingly sickened by profit and speculation. Nature must be loved and respected, but when it is needed, let us trust science and the progress that researchers give us every year with their work.

They kill more grandmothers with their home remedies than scientific and cultural progress, let us never forget that. (Co)science lives in harmony with nature, protects it and enhances it to a better quality.

These are my values.

Cheers 🍷

Chiara