Distillates

History - Production - TypesA distillate is an alcoholic product derived from the distillation of a fermentable sugary liquid usually of vegetable origin.

The distilling technique was already known to the Babylonians and the ancient Egyptians who distilled wine and cider, but it was only around the year 1000, thanks to the Arabs who had perfected the alembic, that at the Medical School of Salerno alchemists and monks began the first distillations of essential oils and alcoholic liquids and used them mainly as ointments and medicines. The alchemists, in search of the philosopher's stone that would make them rich because they could turn everything they touched into gold, distilled the most varied substances. Then someone discovered that some distillates, rather than curing plagues, were pleasant and gave a little cheer in those dark times. The discovery that ageing in wood improved their quality, led the distillates to rest for a long time in small barrels to enrich their aromas and perfect their harmony.

On the labels of bottles of American spirits, in addition to the obligatory alcohol content, there is sometimes an indication in proof (= proof, degree). This expression derives from the fact that in America, from the time of the conquest of the West, in order to assess the alcoholic degree, some gunpowder was wetted with the drink to be tested and set on fire: if the powder burnt completely, it was proven to be rich in ethyl alcohol and low in water. 1 American proof corresponds to 0.5 % of ethyl alcohol, so a 90 proof distillate contains 45 % of it.

Must preparation

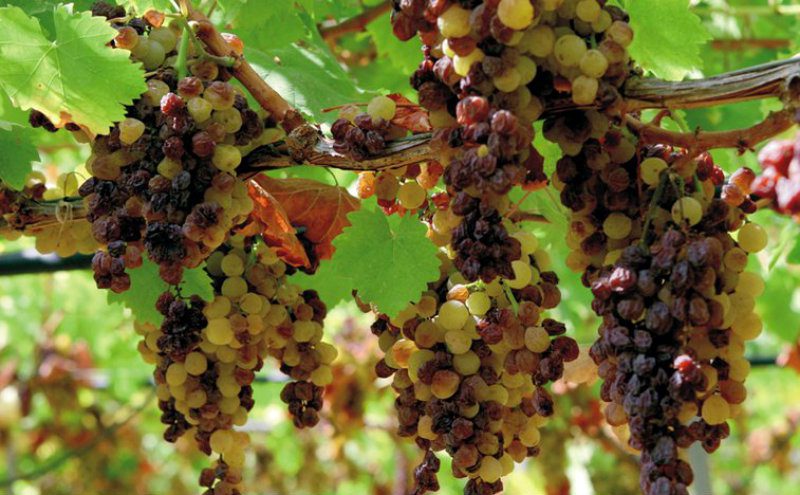

From cereals, tubers, grapes, wine, sugar cane, fruits and honey.

Must fermentation

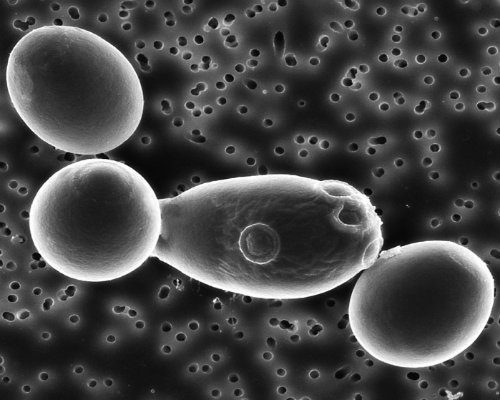

Adding saccharomyces yeasts in 3-4 days yields about 12 % ethyl alcohol.

Distillation

separation of the volatile components of a fermented product due to their different boiling points.

Stabilisation

Barrel rest, dosed addition of distilled water, refrigeration and filtration.

Optional procedures:

Ageing

For some distillates it is compulsory (cognac, armagnac, calvados, whisky), for others it is only a company choice (grappa). The distillate is also put to rest for many years in wooden barrels. Notes of vanilla, spices, tobacco, dried fruit, honey... are the result of the positive action of the wood, both because it allows oxygenation and the consequent formation of esters, and because the distillate breaks down certain substances released by the wood and transforms them into perfumed molecules. For a few years the characteristics of the distillates improve, then the decline begins.

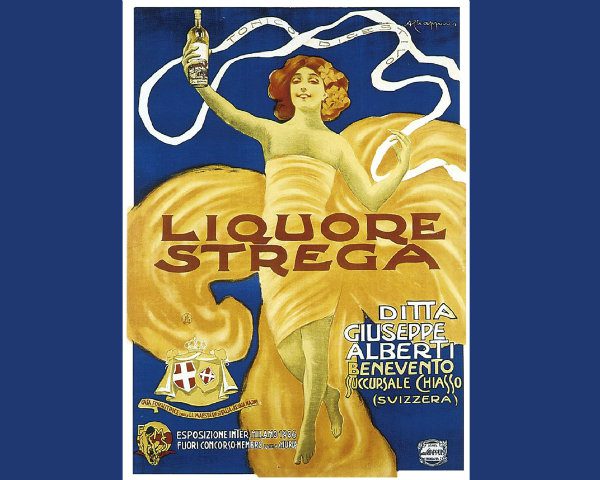

Aromatisation

Those who love spirits reject this practice because it is nothing more than a masking of a poor basic product. However, there are exceptions: Gin, Vodka and Grappa often originate precisely as flavoured spirits. Aromatisation can take place through an infusion of medicinal plants in the spirit itself, which is then distilled, or through the aromatisation of the hydro-alcoholic vapours during distillation (passing through filters made of aromatic herbs).

PHASE 1: WORT PREPARATION

.

If it is from fruit rich in simple sugars, it is enough to crush the fruit to obtain a very sweet juice; in the case of cereals and potatoes (starch, an insoluble and infermentescible complex sugar), enzymes are needed to break down its chains into maltose and transform it into glucose (fermentable). For the enzymes to do their job properly, special temperature and pressure conditions are required (must prepared with hot water or pressure-controlled autoclave processes).

PHASE 2: MUST FERMENTATION

.

Once the must is obtained, selected yeast cultures are added, the Saccharomyces Cerevisiae (saccharomyces, unicellular, osmophilous organisms that are very important for fermentation used in bread-making and the production of wine and beer), which, over a period of 3-4 days at 18 - 25°, produce between 5 - 12 % ethyl alcohol and many other secondary substances that are essential for the quality of the distillate, while many others are released directly by the yeast cell.

STEP 3: DISTILLATION

.

A physical procedure that enables the volatile components of a fermented product to be separated according to their different boiling points with a twofold objective: on the one hand, the ethyl alcohol in the fermented product is concentrated from 5 - 12° % to 65 - 94° %, and on the other hand, the substances that make a distillate valuable are selected and the poor ones are eliminated. There are 2 types of distillation:

- DISCONTINUOUS DISTILLATION = carried out by feeding the boiler intermittently and each load is called a 'crush' and is discharged once it has been used up; the boiler is then refilled with new fermented product. This type of distillation is carried out in pot-bellied, swan-necked copper stills used to produce Cognac, Armagnac, Calvados, Brandy, Grappa and Malt Whisky.

- CONTINUOUS DISTILLATION = carried out by continuously feeding the boiler with fermented liquor, and the distillate is continuously extracted. It is used for the production of Gin, Brandy, Rum, Tequila, grain Whisky and for the industrial production of Alcohol.

First, distillation separates the volatile fractions, mainly water and ethyl alcohol, from the fixed fractions, such as salts and various organic substances. Next, the ethyl alcohol must be separated from the water and the heads (the lighter compounds) and tails (the heavier compounds), which are unpleasant, must be removed from the hydroalcoholic mixture. If it were possible to obtain 100 % pure ethyl alcohol %, there would no longer be any substances capable of altering the organoleptic profile of the distillate, but its personality would also be nullified. This is why, if the fermented product is rich in valuable perfumed molecules, it must be distilled down to 65 - 72° % ethyl alcohol, an interval within which the specifications of many emblazoned producers have included the limit of alcoholic richness at origin. An excellent product never exceeds 75° %, with the exception of Grappa (86° %), Cognac (72° %) and Scotch Whisky (72° %).

PHASE 4: STABILISATION

.

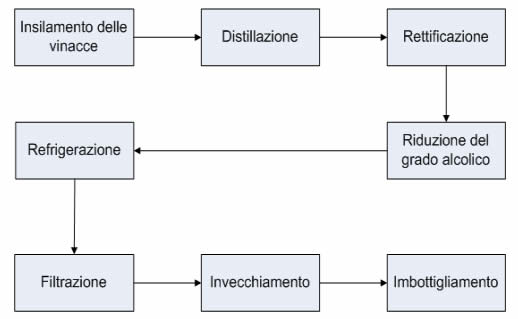

Before bottling, almost all distillates undergo alcohol reduction, refrigeration and filtration. The reduction in alcohol content is achieved by mixing demineralised water that is absolutely odourless, tasteless and low in mineral salts until the desired alcohol content is achieved.

REFRIGERATION at -10°/ -20° for a few hours allows the condensation and precipitation of the heavier substances, generally not very noble and sometimes the cause of turbidity. These are then separated and removed by FILTRATION through cellulose and cotton filters, microscopic fossils (diatoms) and finely crushed rocks (perlites) or microporous membranes.

At the end a RITOCCO is made for which the law allows the possible addition of up to 2 % of sugar to give smoothness and amplify aromatic persistence.

Some claim that the addition of sugar also serves to mask poor distillates, but this is false as adding it would also enhance the defects. Furthermore, the addition of caramel or burnt sugar influences the colour to the point of making even young spirits appear aged, but often brings unpleasant flavours and retronasal sensations.

COMPOSITION OF THE DISTILLATE:

.

Water 40 – 64 % Alcohol 30 – 60 % Sugar < 20 g/l

Methanol = more volatile and maltolerated by the human body (limited to 1% of the total ethyl alcohol)

Higher alcohols = they are often fragrant but sometimes give medicinal notes and must be limited

Foreign = floral notes of lily of the valley and lilac, fruity notes of apple, pear, banana, peach, exotic fruits, dried... (distillates aged for a long time in casks or decades in bottles).

Aldehydes = very numerous. Syringic (pleasant and persuasive), acetaldehyde, valeric (herbal notes)... unsaturated aldehydes can give unpleasant odours.

Ketones = little present (butter aroma) may be responsible for not too fine notes.

Terpenes e Pyrazine = primary spirit aromas because they are derived directly from the fruit used. The most famous of these are those of the Muscat, Gewurztraminer and Williams pear grapes.

Why do I have to concentrate the alcohol to such high values and then dilute the distillate to 40°% ?

.

At a concentration of 40° % ethyl alcohol, even the distillate produced from the finest fermented product would contain excessive amounts of unpleasant tail products.

A TULIP glass, with a capacity of 100-120 ml, is needed to taste a distillate at its best.

TASTING

.

- Visual examination = the distillate flows crystal-clear from the still and must be perfectly brilliant, not least because it undergoes clarification processes to obviate any cloudiness due to ageing or reduction in alcohol content. Most of it is absolutely colourless, while in some cases the substances released by the wood during ageing can give shades ranging from pale straw to amber, with hues tending towards green or reddish.

- Olfactory examination = fundamental in assessing the quality of a distillate. The aromas of a distillate, due to their breadth and complexity, can tire the nose. This is why it is essential to take very short, interspersed inhalations. Intensity, fineness, complexity and balance are assessed.

- Gustatory examination = when taking a small sip of 2-5 ml, only the sweetness (attenuated by the strong pseudo-caloric sensation of the ethyl alcohol) and bitterness (related to copper salts, higher alcohols and substances extracted from wood or flavouring) are clearly perceived. The acidity is hardly distinguishable due to the tactile 'anaesthetising' effect of the ethyl alcohol. Savouriness is only typical of some whiskies. The tactile sensation of roughness is due to the polyphenols extracted from the wood, the higher alcohols and the same dehydrating and burning action of the ethyl alcohol. HARMONY = fusion of refined maturity and smoothness.

- Taste-olfactory persistence (PGO) = very important. With swallowing, the increase in temperature of the distillate promotes the volatilisation of certain substances due to an increase in the evaporation surface. This can last for entire minutes.

SERVICE TEMPERATURES

.

Temperature must be assessed on a case-by-case basis, considering the extreme organoleptic complexity. In Italy, spirits are generally drunk out of habit at too high a temperature.

.

Vodka, Spirits, Steinhager

0 - 4°

Young fruit spirits

6 - 8°

Young Grappas

10 - 12°

Rum. Blended Whisky and Lightly Aged Whisky

14 - 16°

Aged fruit spirits (Calvados), Aged Grappa, Rum, Malt Whisky and Very Old Whisky

16 - 18°

Cognac, Armagnac, Brandy

18 - 20°